Boston may be well-known for change-makers and early champions of social equality like Susan B. Anthony and Abigail Adams. But, did you know that some of the most important trailblazers of the last 200 years were black women? These four fearless females overcame race and gender barriers to create the Boston we know and love today. Here, their stories. …

The Doctor

In 1864, Rebecca Lee Crumpler graduated from the New England Female Medical College (now Boston University School of Medicine) and became the first African-American woman in the U.S. to earn a medical degree. It’s likely that she was drawn to the field after watching a favorite aunt regularly tend to the sick.

An early medical activist, Crumpler brought medical care to underserved populations. She spent time tending to patients in Richmond, Virginia, where she wrote, “The last quarter of the year 1866, I was enabled … to have access each day to a very large number of the indigent, and others of different classes, in a population of over 30,000 colored.”

She returned to Boston to live on Joy Street in Beacon Hill, a predominantly black neighborhood at the time, and then settled for the rest of her life in Hyde Park. In 1883, she published “Book of Medical Discourses,” about her years of medical service. This in itself was a phenomenal achievement; it was one of the first medical publications by an African-American.

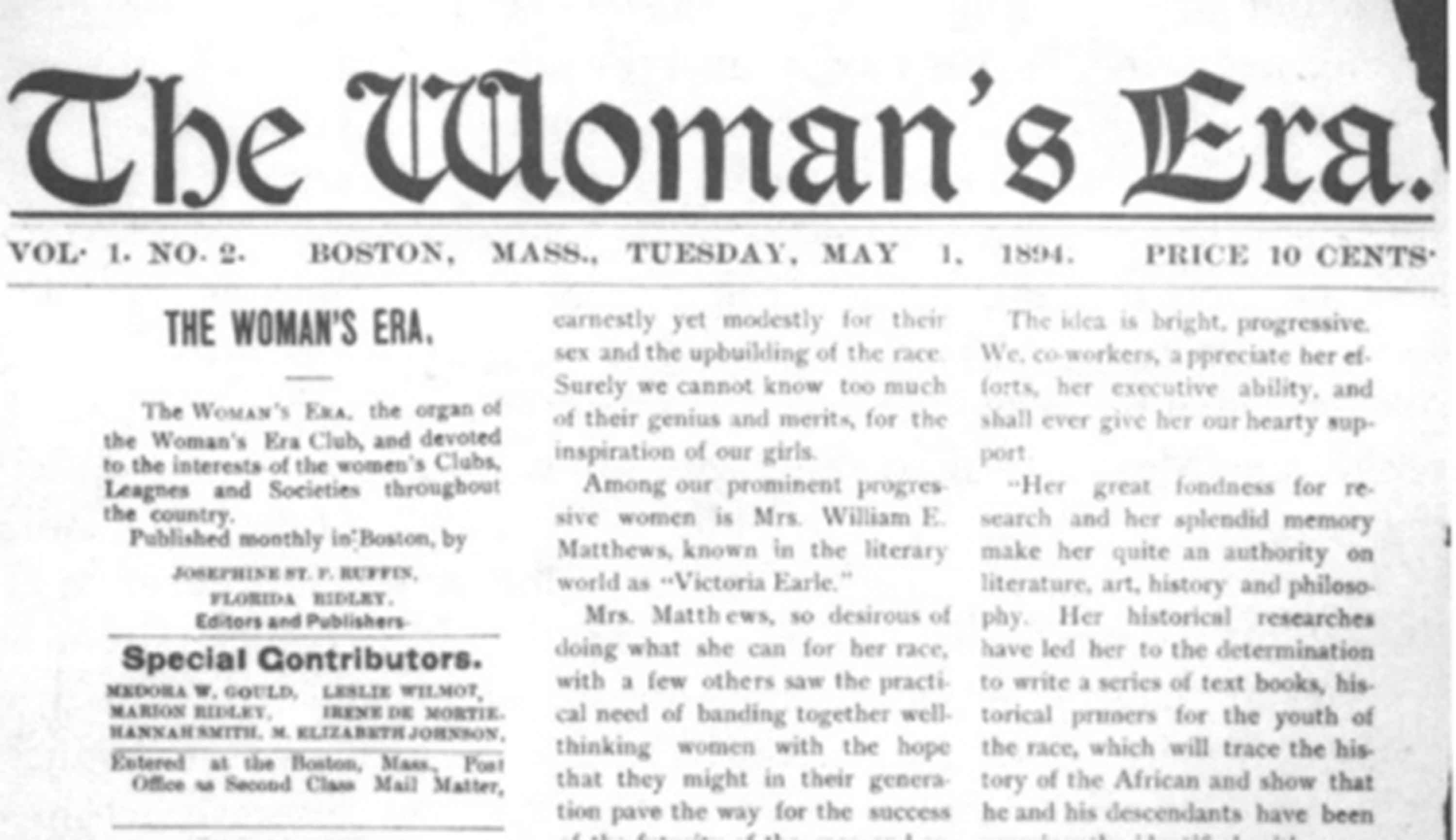

Credit: Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin/public domain/Wikimedia Commons

Ruffin’s newspaper was the first in the U.S. to be published by and for African-American women.

The Newsmaker

Before there was Essence, there was Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin. Born and raised in Boston, Ruffin founded and edited The Women’s Era in 1886. It was the country’s first newspaper published by and for African-American women.

Ruffin was an early advocate for integrating activist organizations, a perspective she held as the daughter of two immigrants, a black father from Martinique and a white mother from England.

But, she didn’t stop there. In 1895, she organized the National Federation of Afro-American Women and worked to promote the achievements of and rights for women of color. After a series of work with other women’s organizations, Ruffin was instrumental in the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1910.

Ruffin’s legacy lives on in Boston, today. She’s one of six bronze busts of influential women on display at the Massachusetts State House and her home on Charles Street (as well as Crumpler’s Joy Street home) is an official site on the Boston Women’s Heritage Trail.

The Writer

When Pauline Hopkins witnessed inequity and oppression as a black woman, she took her anger to the page and the stage. During her lifetime, the activist and author wrote a tremendous amount of fiction and nonfiction about the black experience.

Hopkins was born in Portland, Maine, but she grew up in Boston and executed the bulk of her literary career from Boston and Cambridge.

Best known is her novel “Contending Forces: A Romance Illustrative of Negro Life North and South,” published in 1900 by the Colored Co-operative Publishing Company. Hopkins famously used the romance novel genre to analyze social and racial themes. She’s also attributed with writing the first African-American mystery story, “Talma Gordon.” During this period she was simultaneously working as a writer and editor for The Colored American Magazine.

In addition to her editorial work, Hopkins wrote a musical play called “Slaves’ Escape; or, The Underground Railroad,” which was produced in 1879 when Hopkins was only 20 years old. She performed as a vocalist with her family troupe the Hopkins Colored Troubadours and became a founding member of the Boston Literary and Historical Association in 1901.

Readers can pick up Hopkins’ books at the Boston Public Library to this day.

Credit: Bay State Banner

In 2015, Boston artist Cedric Douglas added a portrait of Melnea Cass to Mike Womble’s “Faces of Dudley” mural in Roxbury

The Activist

If you drive in Boston, you’ve probably, at some point, journeyed down Melnea Cass Boulevard in Roxbury. But, did you know that the street is named after a revolutionary community activist and suffragette fondly known as the “First Lady of Roxbury?”

Cass grew up in Boston and experienced racism and segregation early on when she was denied work opportunities despite her education. These experiences formed the activist force she became in the 1930s. She joined countless nonprofits working towards furthering education and opportunities for African Americans, including the Northeastern Region of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs and the Boston chapter of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

In 1950, Boston Mayor John Hynes appointed Cass the only woman charter member of the anti-poverty agency Action for Boston Community Development (ABCD), which still provides services to assist community members affected by urban renewal efforts. Cass served as president of the Boston branch of the NAACP from 1962 to 1964, and she organized demonstrations against the Boston School Committee’s segregation policy.

4 min read

4 min read