Merritt Moore defies expectations. Being a world-class ballet dancer and a quantum physicist seems like an impossible duality, and yet there she is, a one-off who calls herself a “quantum ballerina.”

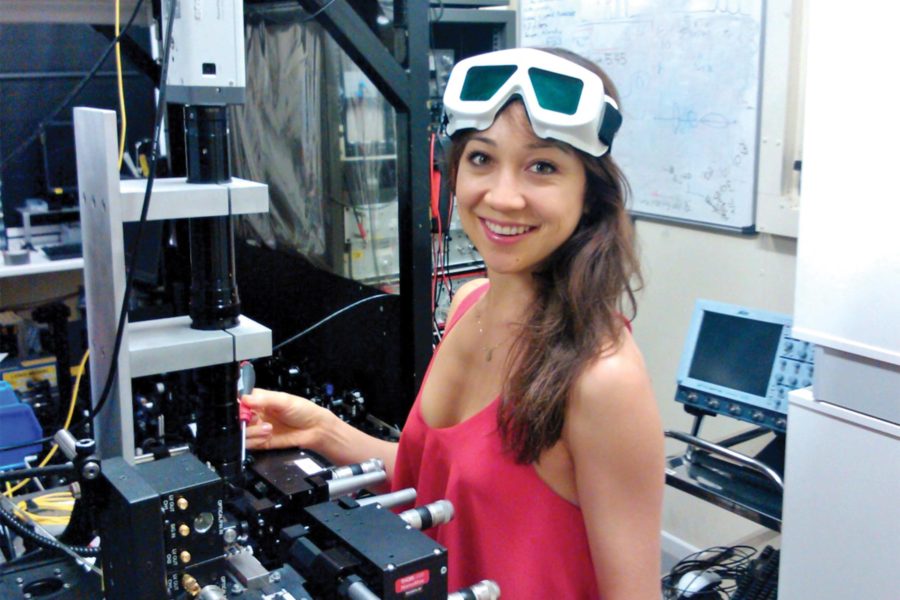

She graduated magna cum laude from Harvard with a degree in physics, and a year ago she completed her Ph.D. at the University of Oxford in atomic and laser physics. Four months later, she was in Oslo rehearsing for “Swan Lake” with the Norwegian National Ballet. Appropriately enough, her thesis work investigated the counterintuitive duality of light in quantum optics: It’s a wave or a particle, properties once assumed to be mutually exclusive, depending on how you measure it.

Defying Convention

For the moment, 31-year-old Moore is a nomad. We’ve caught up with her by phone in Oslo, where she is back rehearsing George Balanchine’s Symphony in C and Natalia Makarova’s La Bayadère. Her day began at 6 a.m., and at 6:30 a.m. she stretched and took a yoga class before rushing to the theater for two hours of rehearsal. After a lunch break, there was more rehearsal and more yoga. By 8:30 p.m. she was back home, eating dinner and soaking her feet in a bucket of ice water. Moore sleeps with her legs propped up on pillows against the headboard to keep them from swelling — she had a recent injury.

In the coming months, Moore might be dancing in Zurich or London, or continuing research she began during an arts residency at Harvard ArtLab, all the while taking piloting lessons and dreaming of becoming an astronaut, after finishing sixth of 12 competitors in the BBC Two’s 2017 “Astronauts: Do You Have What it Takes?”

Moore has defied convention at every turn. While common wisdom dictates that a career in dance requires an early start and that a dancer be performance-ready by age 16, Moore didn’t take her first dance lesson until she was 13 and she didn’t seriously consider becoming a dancer until three years later. Her scientific field of study is one in which women are massively underrepresented. In 2017, the year that she completed her doctoral study, women received only 18 percent of doctoral degrees in physics in the U.S., according to the American Physical Society “Women in Physics.” She’s had few female role models in physics, never having taken a single physics class taught by a woman.

Moore credits her parents for never pressuring her to be anything other than true to herself, and for allowing her to take her time and defy so-called common wisdom. She describes her father, prominent Hollywood entertainment attorney Schuyler Moore, as an accident-prone adrenaline junkie who drives a motorcycle instead of a car and “never walks when he can run.” He might have been a gymnast, but at 19 he broke his neck attempting a double-flip off the swinging rings at Malibu Beach.

Moore’s late mother, Alice Chu-Hoon Moore, died in 2013. She was a rebel who’d shocked her family of Korean academics by marrying, as Moore puts it, “A white guy from America.” Moore and her sister lovingly called her their “Panda Mom.” She stood barely five feet tall — five-two in the high heels she always wore — and Moore remembers her as “super funky,” “super fun,” and so laid-back that she cautioned against “too much pressure” when Moore expressed an interest in joining a soccer team.

There were no Barbies, no television, and no Disney stories in the Moore household.

“My parents filled the house with American football and wrestling, and we had two lumbering Great Danes who’d chase us,” she says. “One room in the house was a library with floor-to-ceiling books. We’d listen to books on tape. Make potions. Work on 3D puzzles.”

James Glader

Merritt Moore transforms ballet into a thing of beauty

Finding Her Way

Moore’s first sport was gymnastics. Though she loved it, “I was too gangly and small boned. I couldn’t cope with all the pounding.” At her mother’s urging, she took her first ballet class as a teenager. “She kind of bribed me,” Moore recalls. “‘Just take five dance classes. Your posture is terrible, and we need to fix this.’”

Moore loved dance lessons and appreciated the teacher’s rigor, but she gave up after becoming convinced, that in order to become a professional dancer, she’d have to be perfect. “I knew I’d never be perfect, because I’d started late. So why bother?”

Discouraged, Moore remembers her father handing her a piece of paper and a pen and asking her to make a list. First, he said, write down what excited her; next, why those things were important to her; and finally, why they were important to others.

Moore spent hours on that little piece of paper. Thinking through her goals, she realized that first and foremost, she did not want to be perfect. What motivated her instead was to explore her own limits and stretch her own capabilities. She wanted to open that door for others who felt like they wanted to explore their own potential.

Those goals haven’t changed. “When I get frustrated,” she explains, “my mantra is I am free, and I give hope.”

Moore returned to dance when she was living in Italy as an exchange student. “Being in a foreign country made me start to question so many beliefs I’d taken as rules.” Like, “People say I can’t dance because I started at 13. Is that really true? Then I met an incredible teacher who became my life mentor.”

That teacher was Irina Rosca, a former prima ballerina with the National Ballet of Romania. “She was so tough,” Moore says. “She was more than just a ballet coach. I’d be beating myself up to be perfect and she’d say, ‘Merritt, stop beating yourself up. Perfect is replaceable. Being unique and individual gives you so much more strength because you are irreplaceable.’”

Moore’s connection with Rosca proved to be transformative.

“So much of what I learned in the dance studio I could use in life,” Moore says. “It gave me more freedom to trust in being me and doing it my way rather than trying to fit in some mold that didn’t feel right.” She returns to Italy regularly to train with Rosca. “I sleep on her kitchen floor. Wake up at six, and she teaches me privately for two hours. She feeds me, I nap, and train some more.”

On a parallel track, Moore studied physics in high school but was not immediately enamored of it. She credits her own tenacity, curiosity, and a lifelong fascination with solving puzzles for getting her hooked on the subject matter, despite the way it is usually taught.

“If they’d told me everything is a quantum harmonic oscillator, I would have paid attention in class.” Instead, she says, “They start with ramps and pulleys — the least useful thing to learn about. We’re taught the equation first and have to regurgitate it on exams. That feels backward. There was no time to visualize or be creative. Einstein had time to imagine and visualize. Only in my [doctoral program] did I learn to ask questions, and a great breakthrough needs a really good question.”

Describing her doctoral thesis on the Oxford Science Blog, Moore wrote that she was “working to create large entangled states of light,” adding to our understanding of how “photons behave when you interfere with them.” Her results have theoretical implications and, in the long term, should contribute to the development of super-fast quantum computers that promise to facilitate scientific breakthroughs.

In all, Moore has taken nine years off from dancing to study upper level physics. “Dancers freak out if they take off one day,” she says, laughing. Her doctoral experiments required her to spend long hours and overnights in the lab, waiting for results. While most of us would reach for our cell phone or read a book to alleviate the boredom, she went for the nearest bannister railing, stretching and working out at the makeshift barre.

These days Moore is fully devoted to dance, and her internalized understanding of the laws of physics informs her every move. When she performs a grand battement — kicking one straight leg into the air from the hip — she thinks about Newton’s law, which dictates that for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. “Instead of thinking of gripping my quads, I push down into the ground with enough force to have the earth kick my leg up. When it comes down, I think about a pendulum’s trajectory. So, I’m not using as much force and muscle; I’m using natural elements of gravity. I can jump quite high, because I have a sense of the center of mass. I’ve done equations of torque so often now that it’s innate and intuitive.”

Paul Gelsobello for Exhale Lifestyle; Moore's top: Lone Reed Designs

Merritt Moore strikes a pose. The physicist and professional ballerina is our Fall issue cover star.

Perspective

Moore has proven herself capable of pursuing two impossible dreams at the same time. Her duality hasn’t been impediment. “Having two passions has helped me focus. I go back and forth.” She sees herself as “that squirrel rat from ‘Ice Age.’ I go after that physics and dance nut no matter how often I fall off a cliff.”

Still, she admits that at times, trying to be both a physicist and a dancer has been a struggle. “Juggling physics and dance, each of which is hard to do alone, never mind at the same time, is hard. I constantly feel as if I had to collapse to one or the other depending on which world I am in, so I never feel whole.”

If she could only do one, which would she pick? Her answer comes quickly: “Whichever I’m not doing! The physical pain of dance makes me appreciate when I can sit with a book doing physics and not be on pointe,” she says. “But, when I’m cooped up for hours and not sleeping, doing an experiment, nothing’s better than being able to stretch out and dance to music.”

Last year, Moore brought her two passions together in the Imagine Science film competition. Paired with a filmmaker Inés Vogelfang, their challenge was to create a short film inspired by science and themed “hybrid-identity.” Particle-wave duality, which Moore had just finished studying for her Ph.D., was the perfect subject.

The video, entitled “Duality,” opens with Moore sliding open an old-fashioned, crisscrossed metal elevator gate and advancing with deliberate, measured steps in her toe shoes to the middle of a cavernous empty industrial loft. Moore’s voiceover is a call to imagination.

“In the beginning of the history of experimental observation (or any other kind of observation on scientific things), it’s intuition which is really just based on experience with everyday objects that suggest reasonable explanation for things. And then we see unexpected things. We see things that are far from what we’d have guessed. We see things that are very far from what we could have imagined. And so as our imagination is stretched to the utmost not as in fiction to imagine things that are not really there but our imagination is stretched to the utmost, just to comprehend those things which are there.”

She takes a moment to look out the window at the city beyond, bends down, turns over a record on a player that sits on the floor, and lowers the needle. Moore starts to dance as the soundtrack — not music but the distinctive, New-York-accented voice of physicist Richard Feynman giving his famous lecture on particle-wave duality — begins.

She moves through the backlit space, her hair flying, her body disappearing and reappearing as she passes between thick Lally columns. She dances, arms outstretched, leaping and tumbling and twirling as Feynman continues his lecture.

When Feynman says, “Suppose that I have an experiment set up so that with the lights out, I get this interference situation,” the lights in the loft go down and beams of light seem to emanate from Moore’s outstretched palms. Her movements become a fluid counterpoint to Feynman’s staccato cadences as he continues.

“And I say that with the light on I can’t predict through which hole it will go. I only know that each time I look it’ll be one hole or the other. The future, in other words, is unpredictable. Why Nature herself doesn’t know which way the electron is going to go.”

He concludes, “We need the intelligence to interpret results. But the important thing about this intelligence is that it should not be sure ahead of time about what must be.”

The essence of wave-particle duality is that it is different each time out. That it is unpredictable. And to understand it, you have to be open to mutually contradictory ideas. This expresses the duality of Merritt Moore, as well.

My final question to Moore is, “In 10 years, where do you see yourself?” Without hesitation she replies, “Dancing on the moon.”

11 min read

11 min read