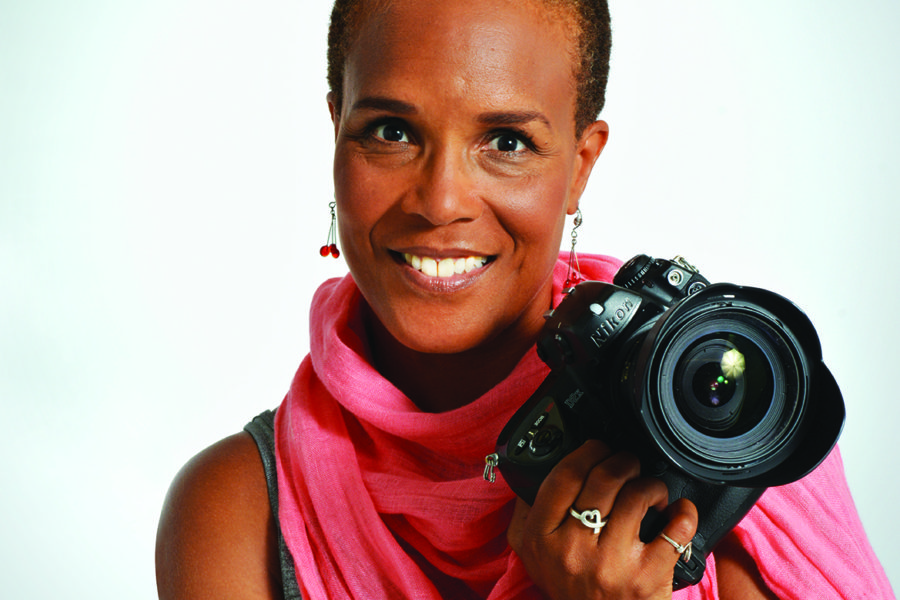

Photo: Don West

Lens crafter: Documentarian Tracy Heather Strain with her camera

Tracy Heather Strain’s dream of making a documentary film about the life of playwright Lorraine Hansberry was a dream deferred but ultimately not a dream denied.

Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart took 14 years to make before its January 2018 broadcast debut on PBS’s American Masters series, resulting in an Emmy nomination this summer and critical praise for Strain and her husband, Randall MacLowry, partners in The Film Posse production company.

The dramatic narrative about Hansberry, activist and author of Raisin in the Sun, unpacks the politics and the personal story of the radical writer who died of cancer at age 34 in 1965, just six years after her signature work brought a potent combination of black family life and civil rights issues to the Broadway stage. Known for her plays, Hansberry also spoke out against colonialism and imperialism, supported gay rights, and worked with leading leftists of the day like actor Paul Robeson and Pan-Africanist W.E.B. DuBois.

Photo: Gin Briggs/Lorraine Hansberry Properties Trust

Lorraine Hansberry speaking at an NAACP rally in June 1959

Strain’s first exposure to Hansberry came at age 17, when her grandmother took her to a local Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, performance of To Be Young, Gifted and Black, a biographical stage adaptation of Hansberry’s writings for the stage. Strain, who wrote stories and poems as a young girl, was immediately drawn in by Hansberry’s creative force field. Less than 10 years later, with the idea of a Hansberry documentary beginning to percolate and heeding Spike Lee’s call for more black filmmakers, she left a career in direct marketing and landed her first job in the film world as a production secretary with Chedd-Angier, working on the television series Discover: The World of Science.

It [the Lorraine Hansberry documentary] was on my shoulders and in my head every day.

Soon, the Wellesley College grad was producing for Henry Hampton’s Blackside—renowned for its Eyes on the Prize civil rights series—and eventually launching her own company with MacLowry. In the meantime, her obsession with a film about Hansberry persisted. “It was on my shoulders and in my head every day,” she tells Exhale. In 2004, in between projects for PBS’ American Experience, she began extensive reading and original research about the Chicago-born playwright and trying “to figure out how to tell a compelling story.”

“I think compounding matters in this case is that there was no major biography out. We did so much primary work ourselves. This is kind of an original narrative,” Strain says.

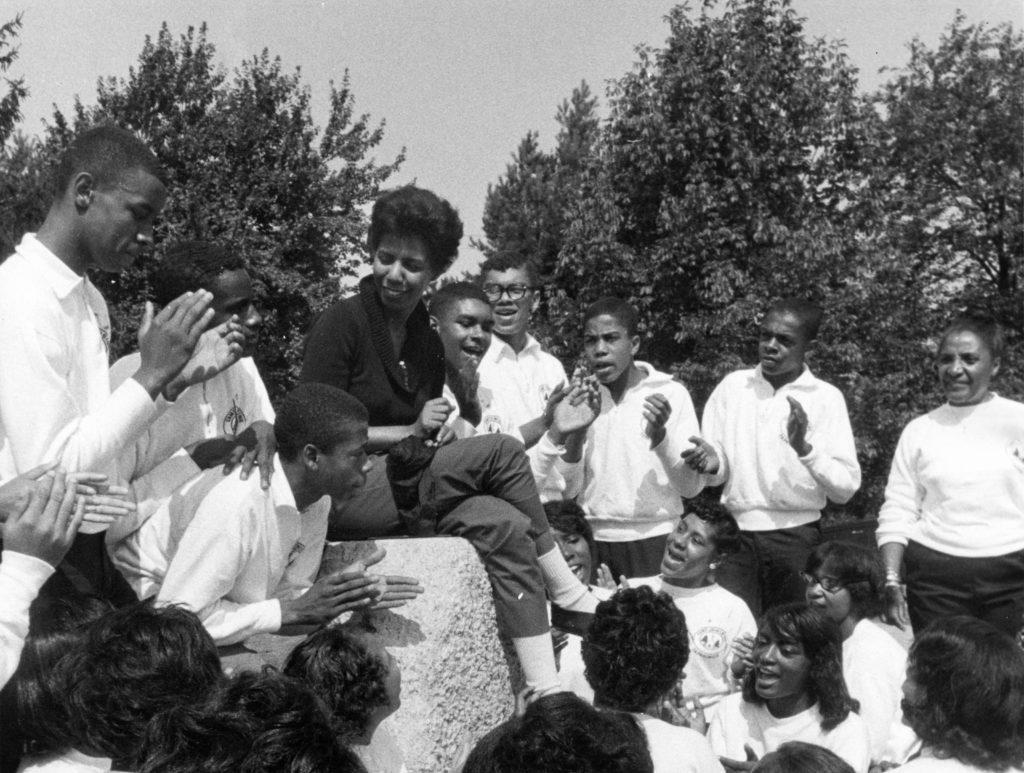

Photo: Gin Briggs/Lorraine Hansberry Properties Trust

Lorraine Hansberry surrounded by teenagers at Camp Minisink in Upstate New York

The Film Posse team, accustomed to intense archival projects, was well suited to crafting a historically compelling film. “The funny thing is both of us were interested in dramatic films, and we end up not only doing documentaries but kind of like the nerdiest end of things—the kind that require a lot of research and digging,” Strain explains.

I think if people really realized that most filmmakers end up in negative numbers like we are now, they would be shocked and horrified.

The work to make a documentary come alive—juggling projects, raising money, and persisting beyond all odds—is invisible to most viewers, especially those who say, “Oh, that’s so cool,” when they learn of Strain’s profession. “I appreciate why they may say that, depending on what they do for a living,” she says. “It doesn’t feel cool. It feels like a lot of hard work. It’s not like you’re getting some financial reward out of it. I think if people really realized that most filmmakers end up in negative numbers like we are now, they would be shocked and horrified. There’s this idea out there that people in media are making bank. That’s why many of us are doing what I’m doing. I have another job. I teach at Northeastern. I have health insurance.”

Running a film company is not purely a creative endeavor. “We are running a business, and making a film itself is like a separate business,” she says. Strain and her husband initially tried doing everything themselves in order to save money without realizing it was more cost-effective to hire a bookkeeper, freeing up their time for other tasks in the production process. She recalls how they would go on a weeklong production trip and return with tons of receipts. “We were literally staying up for days trying to get those things in by ourselves.”

Among other things, learning to delegate allowed the team to raise over a million dollars for the Hansberry project, including a $500,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, a Ford Foundation grant, and funds from a 45-day Kickstarter campaign. She and her husband also sank personal money into the project.

In Langston Hughes’ poem Harlem, the dream deferred threatens to dry up “like a raisin in the sun.” For Strain, support from family and friends kept her dream of the Hansberry documentary from withering away. “I just feel really blessed,” she says of the long journey, “and grateful and relieved.”

4 min read

4 min read