Kolby Knight

Kristin Canty follows an ancestral diet and uses organic food and pasture-raised meats from local farms to supply her Boston area restaurants.

Kristin Canty, raised near the first battlefield of the American Revolution, has launched a food insurgency aimed at changing the way we eat. The vanguard of the attack to restore our ancestral diet of pasture-raised meats, wild seafood, soaked grains and organic vegetables is her gourmet Woods Hill Table restaurant in West Concord, Massachusetts, located upstream from the iconic North Bridge where the embattled farmers fired the shot heard ’round the world.

Just down the street from that popular eatery is another of Canty’s: Adelita, her more modestly priced margaritas-and-tacos bar named for the archetypal warrior-woman of the Mexican revolution, which follows the same farm-to-table principles of healthy eating as superb cuisine.

Both restaurants make everything from scratch and serve poultry, lamb, pork and beef sourced from Canty’s 265-acre Bath, New Hampshire, farm, named, simply, Farm at Woods Hill. She also sources produce and meat from other small farms conforming to her tabletop manifesto.

The next garrison in her nutritional war is Woods Hill Table at Pier 4, a 240-seat restaurant scheduled to start seating hungry diners on the Boston waterfront in the fall.

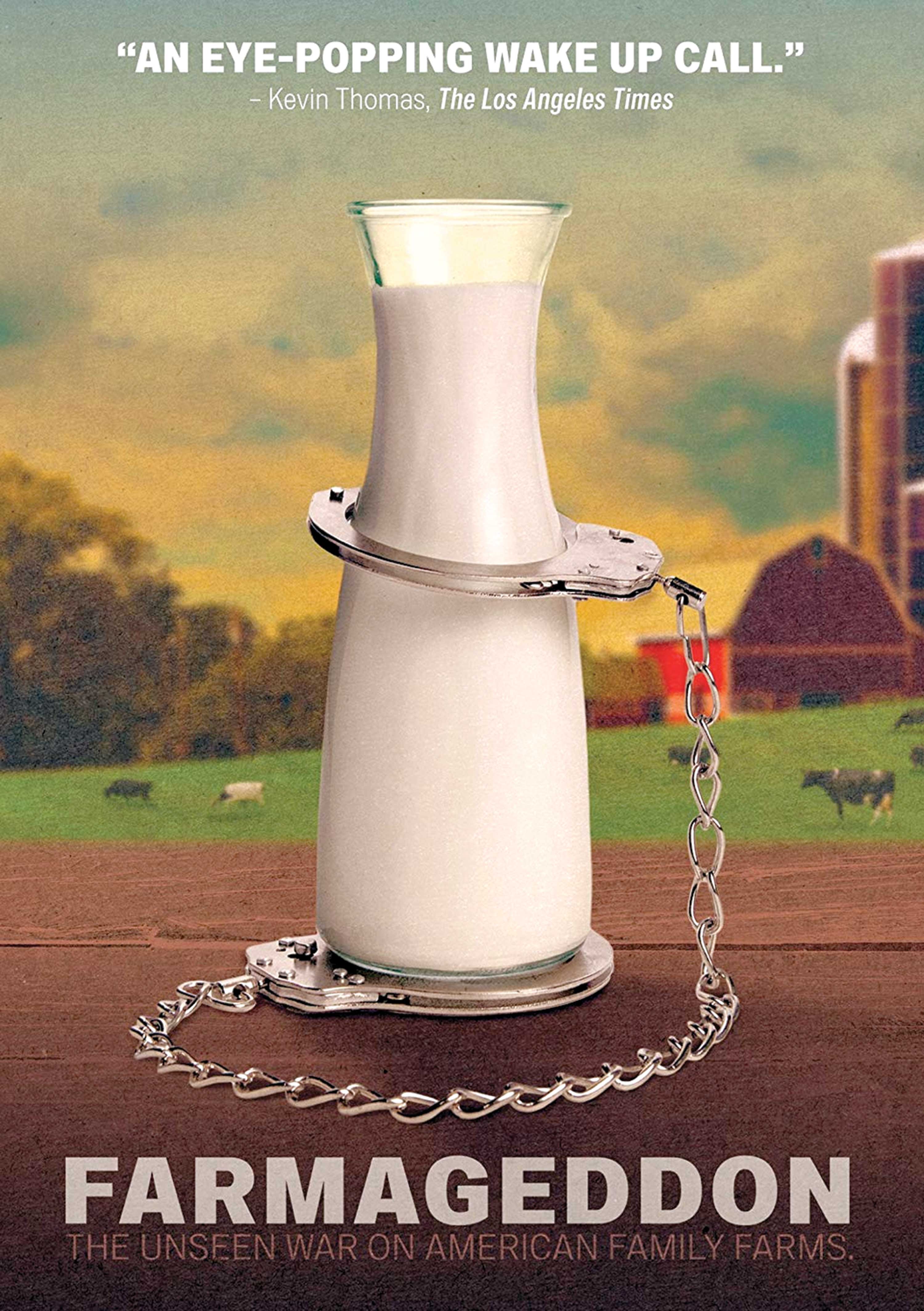

Meanwhile, providing steady reinforcement is Canty’s self-produced documentary, “Farmageddon: The Unseen War on American Family Farms,” released in 2011 and widely available on streaming services. It chronicles the struggles of organic family farmers harassed by government agents in cahoots with shadowy agri-business interests.

Canty, smiling beneath brunette bangs as Saturday brunch customers walk into Woods Hill Table, seems like an unlikely rebel. Customers follow the slender restaurateur, clad in a bohemian black silk mini-dress with billowing sleeves, to tables beneath iron-and-leather custom chandeliers and salvaged barn-wood beams. Slipping into a booth at the back of the light-filled room, Canty brushes back a single lock of hair to share the story of how she took up arms — and farms — against a sea of factory-produced foodstuffs.

“My son was diagnosed with being allergic to the world,” says Canty about Charlie, the third of her four children, who was born in 1995 and developed severe allergies at the age of four.

“My son was diagnosed with being allergic to the world,” says Canty about Charlie, the third of her four children, who was born in 1995 and developed severe allergies at the age of four.

“He was allergic to grass, dust, every animal. He couldn’t breathe; he couldn’t sleep. It was a nightmare taking care of him, following him around the house with an EpiPen and an inhaler.”

Her voice, soft yet with intense conviction, conveys the emotions of a distressed mother. Consulting top physicians at leading hospitals with Charlie and her newborn fourth child in tow, Canty “got a different medication every time, and each doctor would tell me the last one was incorrect.”

Canty finally gave up on pharmaceuticals. She ripped up the carpets in her home, threw away the drapes, got rid of the pets, sprayed for dust mites, and began to research possible causes of severe immune depression.

“I found out that kids who grow up on farms don’t get as many allergies as kids who don’t,” she says, “and that adults who had allergies their whole life found a cure with unpasteurized milk.”

I found out that kids who grow up on farms don’t get as many allergies as kids who don’t,” she says, “and that adults who had allergies their whole life found a cure with unpasteurized milk.

Courtesy Kristin Canty

With little media experience, Kristin Canty first spread her revolutionary message through a documentary she created, “Farmageddon: The Unseen War on American Family Farms.”

The idea of drinking raw milk disgusted her, but the data was compelling. So, she tried it herself and gave it to all her children. “Charlie stopped sniffling, and I didn’t really believe it was the milk at first. But, then it was three months, and then it was six months, and then a whole year went by, and we exposed him to animals, and we realized, like wow, this kid hasn’t had any allergies. It took us at least a year to accept the fact that he was cured.”

Trained as a speech pathologist, Canty, by then, had set aside her career to raise her family, child care costs having outpaced her earnings. She became increasingly drawn into the natural foods community, joining meat and milk clubs and community-supported agriculture co-ops.

Canty got involved with the Weston A. Price Foundation, which promotes a nutrient-dense diet, including fermented foods like sauerkraut and kimchee, based on the menus of our ancestors. The passion of the new convert flamed even higher as she learned about family farms raided by gun-toting federal and state authorities bent on shutting down raw milk and organic food clubs on flimsy pretexts with little accountability. After hosting a fundraiser for the Farm to Consumer Legal Defense Fund, Canty decided the public needed to hear the stories of idealists dragged through courts, their products confiscated, livelihoods shattered, and customers denied access to healthy food.

Canty approached a seasoned documentary filmmaker. Instead of taking up the project, he advised Canty to produce it herself. “I said, ‘Are you joking?’ I had four little kids at the time.”

But the revolution had to be televised.

“A week later, I had created Kristin Productions LLC, hired a film crew, booked the interviews, and booked the flights,” she says with a shrug. Canty flew around the country to talk to farmers like Mark Nolt of Newville, Pennsylvania, led away in handcuffs for selling raw milk out of his barn, and Jackie Stowers, whose rural Ohio co-op was shut down after a SWAT-team raid.

The movie’s ominous soundtrack and blurred cutaways in the raid scenes evoke deep-state conspiracies and black helicopters, while footage of the farmers at work, bathed in sunlight and backed by finger-picked guitars, leave no doubt about the heroes and villains of Canty’s video tale. She appears not only as a narrator, but also as a nervous interlocutor trying to wring the truth out of a reluctant flack for a state agricultural agency.

“Farmageddon” isn’t subtle, but it is effective. Picked up by Gravitas Ventures and Warner Brothers, it has thrived in five languages. Canty says, “People write to me and say it’s made a difference in their lives, even if they’re only shopping at farmers’ markets.”

People write to me and say it’s made a difference in their lives, even if they’re only shopping at farmers’ markets.

Picking up a pitchfork became the next step in Canty’s assault on the battlements. With an eye on opening an eatery to put her nutritional principles into practice, she bought the Woods Hill Farm in 2013. Dating back to 1794, the Granite State property has houses and barns, a lodge for paying guests, pastures and forest cover, and plenty of oaks offering shade and acorns for rooting hogs, shoats and sows. The farm, located near the Connecticut River and 150 miles north of Boston, has 85 cows, 120 pigs, a handful of goats, thousands of chickens and ducks, and 40 ewes and 40 lambs. “Our director of homeland security is a llama,” says Canty with a laugh. “We call her Michelle Ollama.”

White Loft Studios

Canty’s working New Hampshire farm.

Woods Hill Table found its home when Canty purchased the old, family-run West Concord Supermarket, just a mile walk from where she grew up. Her partner was her father, legendary investment manager Charles I. “Chuck” Clough, Jr., an ordained Catholic minister and philanthropist known during his New York days with Merrill Lynch as the “Deacon of Wall Street.”

Canty’s original concept of a farm-to-table diner evolved into a full-service, 153-seat restaurant featuring fare for the rustic sophisticate along with solar panels on the roof and green-and-white striped awnings to preserve the look of the old market. Inside, a steak-house décor, with a long bar and wood-burning fireplace, belies an award-winning menu that digs deep into culinary history and has attracted a full house since its opening in 2015.

Massachusetts-raised chef Charlie Foster, a veteran of top Boston and Manhattan kitchens, serves buttery meats, inventive seafood, and delectable side-dishes like tallow-cooked potatoes and wood-grilled broccoli to a clientele of local celebrities and loyal customers. Even Hollywood has gotten a taste as actress Laura Dern made repeat visits while filming “Little Women” in town, based on the 19th-century novel by famed Concord author Louisa May Alcott.

Canty’s favorite dish is steak tartare — like all her meats, free of hormones, antibiotics and feed made with genetically modified organisms. She also loves the seafood and oysters. The restaurant’s fishmonger advises Foster on the best options for freshness and sustainability, so that regenerative farming on land is matched by harvesting practices at sea in such nutritious choices as monkfish, bluefish, mackerel and pollock.

White Loft Studio

Kristin Canty’s West Concord restaurant, Woods Hill Table.

Over at Adelita, opened in 2018, Foster draws from his wife’s Mexican origins to serve zesty street food, from tacos to quesadillas and tostados prepared with artful garnishes like avocado cream. Not to be missed is the mouth-watering grilled street corn with cotija cheese and aioli.

Canty, who waitressed during college in bars and pubs from Cape Cod to County Clare, got a certificate in restaurant management from Cornell before opening Woods Hill Table. She usually arrives before noon and stays until closing, except when spending time at the farm or traveling. The wearying demands of building and running four businesses simultaneously haven’t become any easier since losing her husband Jim to brain cancer two years ago. After his diagnosis, Jim and their large extended family encouraged Kristin to keep moving forward, pursuing a mission larger than just a dining experience.

Canty’s hands lie palms-down on the table in front of her. “How did I do it?” she asks. “Lots of positive thinking. What else can I do? I could sell it all and just fall apart or keep going.”

Canty’s hands lie palms-down on the table in front of her. “How did I do it?” she asks. “Lots of positive thinking. What else can I do? I could sell it all and just fall apart or keep going.”

“And, to be honest,” she adds, “Dr. Joseph Dispenza. I just listen to him every day.”

Canty has just returned from a spiritual retreat with the holistic healer, and embraces his advice of “living in your future and not in your past. And, healing your body. Just to keep going.” Riding at her farm also helps, providing equine therapy.

Diana Rodgers, a licensed dietician who lives on an organic farm and runs Sustainable Dish, a Massachusetts-based non-profit consultancy and podcast, has worked with Canty for over 10 years in food activism.

“Kristin is one of the most generous, dedicated, passionate people I’ve ever known,” she says. “She works tirelessly through her film, advocacy, farm and restaurants to create a regenerative food system. I can’t think of a better leader for the real food revolution.”

White Loft Studio

The farm-to-table food at Kristin Canty’s restaurant Woods Hill Table is as beautiful as it is delicious.

Canty’s next venture at Pier 4 is a dramatic departure from bucolic landscapes and small-town dining. Her restaurant in New England’s culinary capital occupies a storied space in gustatory history—the site of Anthony’s Pier 4 gabled lobster shack, famous for its popovers and Mad Men-era celebrities like Elizabeth Taylor and Frank Sinatra rubbing shoulders with Boston pols like President John F. Kennedy and Boston Mayor Kevin White. The building is gone, torn down to make way for a nine-story condo tower in the rechristened Seaport District, where Canty’s ground-floor restaurant will face water on three sides through floor-to-ceiling windows and every seat has a water view.

“The décor is light and bright and breezy,” says Canty. Like the others, it will feature grass-fed meats and locally sourced provisions prepared under Foster’s expert direction.

“She’s a real warrior,” says Michael Goodwin, a longtime family friend who is collaborating with Canty on food programming connected to his innovative “Rivers and Revolutions” school-within-a-school curriculum at Concord-Carlisle Regional High School. “Our program, at its heart, is about uncovering connections. There’s something really similar going on at her restaurant.” Goodwin, whose mother, historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, is a frequent diner at Woods Hill Table, taught three of Canty’s children and admires her interdisciplinary approach to the business.

“Many of my students have worked for her, and they appreciate learning all the parts of the organization and being treated with respect. I watch Kristin work her magic, not just welcoming everybody, but making them part of what’s going on—part of a much larger message and mission.”

Canty frames that mission succinctly. “I’m very happy about serving this food,” she says, “taking care of farmers, being an advocate for farms, and teaching people how to eat good food.”

The driving spirit of her food revolution is to reconnect people with nutrition, to understand where food comes from and the importance of choosing wisely what you eat. “As long as we stay disconnected from our food,” she adds, “we’ll have factories feeding us.”

11 min read

11 min read